Renee Linyard-Gary

Director of Diversity, Inclusion and Health Equity, Roper St. Francis Healthcare

Former Director of Health, Trident United Way Charleston, South Carolina

Advice for Upstreamists

“A big key component of the work is listening. Taking a step back. Working with your community partners and stakeholders, and listening to what truly are the needs of the community or program where you’re trying to serve a targeted group or population. Second to that, I think there is strength in being collaborative—hearing from different individuals, hearing the community voice, building the opportunity for people to convene and share their feedback is very important…I feel like it leads to greater impact when it is truly a collective approach.”

The Big Idea

How do you move a large, diverse group of stakeholders—each with their own work and mission—from intention to collective action around health equity? In 2019, this question was front-of-mind for Renee Linyard-Gary as she and Trident United Way coordinated efforts with organizations across three counties in the greater Charleston area to begin implementing a state health improvement plan locally.

For years, health equity work in South Carolina had largely been done in silos that led both to blind spots and duplication of efforts. Then in 2019, stakeholders from health care, social, and public health sectors statewide began developing the South Carolina Roadmap to address Social Determinants of Health, which identified shared goals to improve health equity by addressing underlying community-wide social, economic, and physical conditions. The goals focused primarily on reducing food insecurity and housing instability, and doing so in ways that reduced social isolation and structural racism.

Getting so many different communities and stakeholders to identify and agree on a handful of opportunities for improvement was critical, but it was just a first step. Taking collective action to actually meet those goals required breaking down those large goals into smaller action steps and engaging stakeholders to sustain cross-sector collaboration.

The Details

Renee Linyard-Gary’s Journey

Renee Linyard-Gary spent her early career seeing health care from different vantage points, as a pharmacy tech, in a practice management role, and in business and data analytics for a healthcare company. In each of these roles, she saw how social barriers affected health and access to health care. And then she experienced some of those barriers herself when she lost her job in the Great Recession in 2008 and was uninsured. This caused her to pivot and start working on health issues at the community level. She became the program director of the access to care program housed at Trident United Way, overseeing prevention programs and working directly with communities and clients to identify their needs. In part, it is her experience and perspective working in so many different sectors that helps her engage community, health care, and research partners in equity work. (More recently, Linyard-Gary has become the director of diversity, inclusion and health equity at Roper St. Francis Healthcare. This story centers on her work at Trident United Way.)

The Intervention

One of the Roadmap’s main goals is to reduce food insecurity, including racial disparities in food insecurity, statewide by 30 percent by 2023. But to make that goal achievable, it needed to be broken down into specific projects and action steps. To help do this, four regional teams participated in HealthBegins’ South Carolina Roadmap to Food Security Community-Based Learning Collaborative. Linyard-Gary and Trident United Way headed up the Healthy Tri-County team, alongside partners from Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC).

The Healthy Tri-County team had a head start coming into the learning collaborative. In 2016, Trident United Way partnered with Roper St. Francis Healthcare and MUSC to conduct a community health needs assessment, work which eventually led to the creation of a regional initiative with more than 90 cross-sector organizations aimed at collectively addressing issues identified in the assessment. The partners developed a regional, five-year health improvement plan, shaped by community input, and created workgroups to support its goals. So when the work on the statewide Roadmap and the learning collaborative began, Linyard-Gary and her team had both the expertise and buy-in of food banks and other organizational partners. The Roadmap provided the opportunity for the regional partners to build on work they’d already begun, with state-level support. However, they still needed help fine tuning an action plan.

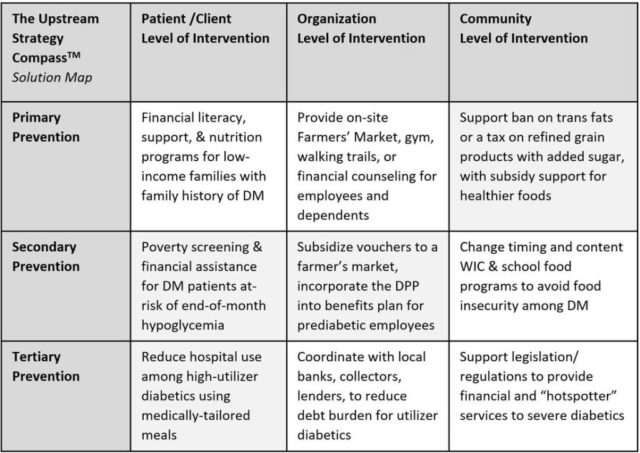

As part of the learning collaborative, teams used HealthBegins’ Upstream Strategy Compass™ to brainstorm specific solutions that would build upon, align, and accelerate current efforts to improve food security. The tool specifically guides users to look at potential solutions at three levels—individual/household, community, and societal/structural—and to think about each at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of prevention.

Linyard-Gary said that the goals outlined—first at the regional level and then in the statewide Roadmap—were like a compass, and that using the tool to break down smaller strategies was the equivalent of charting the course. The tool gave them a process by which they could dissect what they were already doing, see what was missing, and prioritize strategies that would be most effective. The tool also got the team thinking more about statewide and structural solutions, which had previously not been as much of a focus. “The community was kind of eager for that kind of conversation, because we’ve been talking about the planning and implementing and monitoring,” said Linyard-Gary. “But giving them tools to take back about how to do that at wherever they were in this work … what could they do, where they were? And that was the biggest takeaway, is do what you can, where you are.”

The team from Healthy Tri-County identified three priority steps toward reducing food insecurity, including to implement Foodshare, a free or low-cost fresh food box program, screen for food insecurity within the electronic health record at targeted MUSC primary care clinics, and secure investment to support an SDoH Accelerator Plan in Charleston focused on built environment and food insecurity.

The Impact

Healthy Tri-County has already met many of the smaller goals related to equitable food access that it set during the learning collaborative. In December 2021, Foodshare, led by Trident United Way, began implementation in Berkeley County. In fall 2021, the identified MUSC Health primary care clinics launched a pilot to screen for food insecurity within the electronic health record. Patient navigators were also embedded in those clinics to address the needs uncovered with the screenings. Next, Healthy Tri-County is looking to fully implement the FoodShare pilot and is also exploring community garden projects in neighborhoods with large BIPOC populations.

Lessons Learned

Getting the more than 90 organizations that are part of Healthy Tri-County to plan and act together—both on this food insecurity work and other health improvement projects—is an ongoing process. Here are three lessons Linyard-Gary shared about keeping partners engaged while helping this type of coalition work effectively and deliver results.

1) Get commitment from the c-suite level not only to participate, but to take action.

“You can’t move this model if you don’t have support from the c-suite level of organizations to say, ‘yes, go forth, and keep them engaged,’” says Linyard-Gary. Each of the nearly 90 organizations that are members of Healthy Tri-County has signed a pledge at the executive level to identify a representative to participate in a workgroup and to either participate in a campaign or co-sponsor an event. She stressed the importance of understanding each partner’s specific agenda—the mission of their organization, their goals for participating in a project, and their strengths and weaknesses—and checking in regularly. Linyard-Gary meets with VPs, chief diversity officers, or community health officers from these organizations on a monthly basis to get their feedback and input.

2) Create forums to regularly engage people from different sectors as often and early as possible.

Healthy Tri-County meets every other month with all stakeholders to share updates from subcommittees and projects. It’s also a chance for organizations to get instantaneous community consultations. For example, researchers from the local academic institution have come to get feedback from the various sectors about how they might make adjustments to a new research study or how to introduce a new community project.

During the learning collaborative, the team also organized “think tank sessions” with local partners and other regional learning collaborative teams in the state to discuss the work and learn from each other. “The think tank sessions and thoughts were fresh ’cause we can get bogged down into the weeds of our work,” Linyard-Gary says. “But sometimes fresh eyes help us move to the next phase of it, and I felt like that was very helpful.”

3) Keep the goal at the forefront and celebrate wins.

A big part of keeping community members and partners engaged is keeping goals at the forefront of conversations, especially when you are in the weeds of implementation. “Many times we find that in those opportunities to plan, do, and act, we have to always kind of go back to what our goals are,” said Linyard-Gary. “Where are we trying to get to? What are the results at the center? And to maintain that engagement that we have from the time we’re listening through the times that we’re getting to action.”

As part of that effort, she stressed the need to celebrate and call out successes, especially early wins. She notes that it keeps people focused, interested, and open to further action. Calling out successes also contributes to trust, especially with the community. They are proof points of progress.

Kate Marple is a Boston-based writer who specializes in helping nonprofit, health care, and legal services organizations develop practices to ensure that the stories they tell are shaped by and benefit people directly impacted by the issue(s) those stories are about. Her website is https://whotellsthestory.org.

Learn how HealthBegins can help you move healthcare upstream. Contact us to learn more.

Featured Content

How to Read the New Federal Dietary Guidelines as a Health Equity Advocate

The new Dietary Guidelines released by the Department of Health and Human Services not only run counter to established health standards, but also against health equity goals. Here are the the issues with these guidelines and what actions health equity advocates can take for better outcomes.

Small Practices Improve Health and Health Equity in Big Ways

The EQuIP-LA effort led to statistically significant health improvements and highlighted lessons that could help amplify the impact of small practices in advancing equity in more places.

Building Community to Improve Maternal Health: Lessons from Group Prenatal Care

HealthBegins supported health centers across the country to find new ways to make maternal health more equitable and effective. The solution was Group Prenatal Care—a means of fostering community as part of the care—and the outcome was nothing short of inspiring.