This is Part 2 of our series about the work between Cone Health and the Greensboro Housing Coalition. You can also view Part 1 here and Part 3 here.

Most health systems today engage in some form of health equity work, but few do so in true partnership with the people they mean to elevate, where residents’ priorities actually dictate hospital practices or are used to hold them accountable. Few, too, reckon with the role their institutions have played in creating inequities in their communities in the first place. Cone Health in Greensboro, North Carolina, is beginning to do that. And as it is learning, acknowledging the past is the first step in becoming an authentic and trustworthy partner in this work—and a prerequisite to finding meaningful ways to lift up and center community voices in its decision-making and systems of accountability.

The Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital is located just two miles down the road from the Woolworth lunch counter where, in 1960, four Black college students staged a sit-in that sparked a national movement. Present-day disparities in Greensboro continue to be shaped by a legacy of structural racism, discriminatory policies such as redlining, and a history of segregated businesses and institutions like the one those young students were protesting. Moses Cone Memorial Hospital itself was segregated until 1963, when a lawsuit filed by six Black physicians, three Black dentists, and two Black patients went all the way to the Supreme Court to change that. Their landmark case paved the way to end segregated health care across the United States. Moses Cone Memorial Hospital quietly integrated, but for more than 50 years, that history went largely unacknowledged by the health system.

In 2010, a shift was taking place inside Cone Health, which serves more than 400,000 patients a year between its five hospitals, four medical centers, six urgent cares, and more than 100 physician practice sites. Two questions were driving its transformation: How do our employees see our culture and priorities? and How does our community view us? A system-wide staff survey surfaced two core issues: the health system’s metrics prioritized finances over patients, and there was significant work to do around addressing racism within the organization. At the same time, focus groups with community members shone a light on just how deeply the health system’s history was still felt. As HealthBegins has learned through work across the country, health system leaders and staff must actively and authentically listen to community members to truly understand the pervasive, residual impacts of redlining and institutionalized racism on health equity for their patients and communities.

Seeing the health system through its staff’s and community members’ eyes was the impetus for Cone Health to formally begin diversity and inclusion and then health equity work. “I really feel like we had to hold up the mirror and see who we were and change who we were being in order to do something better,” said Laura Vail, systemwide director for population health equity at Cone Health. “There was some really good work starting to be done inside the organization in terms of our own accountability. But as we looked toward the actions that follow that accountability, the question was, ‘How do we take the first step in redressing and reversing actions that, as an institution, we had been involved in that led to present day inequities in health?’”

In 2016, that first step toward accountability in action was to acknowledge the history that had been quietly swept under the rug five decades earlier and to apologize publicly to the community and to Dr. Alvin Blount Jr., the last living plaintiff from the lawsuit. The second step was to listen more deeply to the communities most affected by that history and better incorporate community voice into the health system’s decision-making going forward.

“We now see our role as being a ‘conduit to good health’ instead of being in a powerful position of ‘we deliver the good health,’” said Vail. “We are a conduit of good health, and those things happen through partnership.”

Three Ways Cone Health Is Elevating Community Voice in Decision-Making

Apologizing for its past—not just once publicly, but multiple times in a variety of smaller, more intimate settings, as Vail did recently during a HealthBegins-facilitated workshop with colleagues from other health systems—and acknowledging its role in contributing to health disparities in Greensboro, has been a major factor in shaping the type of action it takes moving forward. Cone Health knows it can only succeed on equity if it works side-by-side with community members and leaders themselves. And it can only do that if it has a genuine relationship with community members who see, not once but repeatedly, that their voices really count. Here are three of the ways Cone Health is trying to do that.

1) Identifying and tackling health inequities

One of the first steps Cone Health took was to more explicitly track and analyze patient data by race and ethnicity across the health system—both to better identify who was experiencing inequities in care and to map inequities geographically and detect patterns that they could work with community partners to redress. Cone Health, as part of HealthBegins’ Social Drivers of Health Equity Learning Collaborative, is currently leveraging data to pursue a three-pronged strategy: (1) identify what medical conditions drive self-pay patients to seek care in the emergency department (ED), (2) identify racial and ethnic inequities in ED utilization, and (3) remedy underlying social and structural drivers of these inequities in avoidable ED visits. More and more, the health system is prioritizing and taking part in community-based participatory research, where communities affected by the issue being studied are involved in all areas of research design, implementation, and action.

From 2013-2018, Cone Health Cancer Center was part of a five-year study led by the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative to test interventions to enhance racial equity in the completion of lung and breast cancer treatment. Interventions included explicitly tracking data by race and creating alerts for missed care milestones, providing feedback to clinical teams on completion of care according to race, and providing explicit bias and anti-racism training for nurse navigators and physicians. The interventions improved treatment completion for all participants and mitigated Black-White inequities in cancer treatment. They also led to lasting changes in how Cone Health delivers cancer care.

2) Designing healthcare services and spaces with explicit input from community members

Cone Health uses human-centered design thinking to focus on getting consumer and community input on new services and facilities. The health system recently opened a new medical center for women located deeper in the community than many of the facilities it has built in the past. The health system worked closely with residents to think through every aspect of the space—from the services and resources that would be available there to its size and what art goes on the wall. Vail said their goal was to “ask people about everything, and learn what access feels like to someone else.”

The feedback residents shared transformed the plans for the space. Community members asked for access to food, so Cone Health included a “food pharmacy.” Pregnant residents asked for prenatal and postnatal yoga classes, so rooms were built specifically for education and exercise classes. New mothers asked for dyad appointments for themselves and their babies to reduce the number of trips they made for health care, so the new medical center started offering them.

3) Listening to and getting involved with efforts led by grassroots organizing groups

Vail said health systems commonly assume that patients’ biggest concerns are around access to care inside the hospital, but when Cone Health started listening more, they learned their patients were often more concerned about things happening outside the walls of the hospital—like jobs, transportation, and housing. So, at the same time that Cone Health started to look at issues of equity in care delivery, it also started asking what it could do to address factors outside the walls of the hospital. To do that, the health system needed to get close to the community by building relationships with people living in the neighborhood and with grassroots organizing groups.

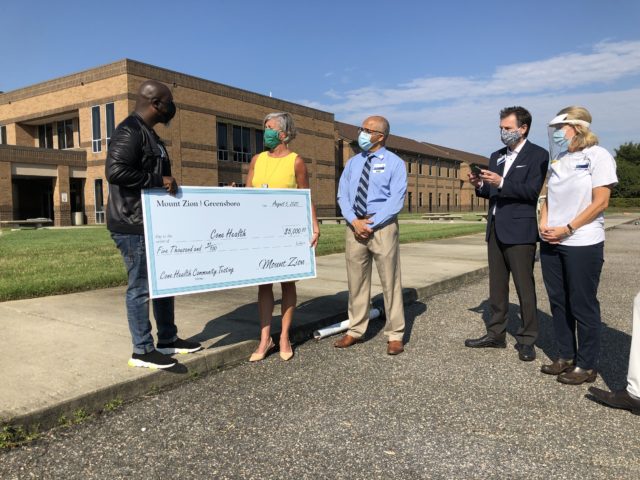

In 2018, residents in the Cottage Grove neighborhood built a coalition that improved childhood asthma by mapping and rehabilitating substandard housing units. Community leaders spurred Cone Health to play an active role in the coalition. In fact, its participation started years earlier, when Kathy Colville, Cone Health’s then-healthy communities director, began attending neighborhood association meetings to listen and learn from residents. Colville’s presence at those meetings, and the trust she slowly built with community leaders like Josie Williams, executive director of the Greensboro Housing Coalition, were essential to Cone Health’s ability to contribute effectively to the coalition.

Lessons Learned

Vail is the first to say that Cone Health’s work to elevate and center community voices in their decision-making is a journey, one that is far from over. But the health system is listening, trying new things, and adjusting along the way, each time learning important lessons that they carry into the next project. Here are three of the takeaways Vail shared.

1) Be transparent and accountable for change.

“[Health equity work] is about compassion and it is about justice, but if you stop there, there is nothing to trust in,” said Vail. “You have to take action. You have to do something. And you must make it explicit. And that’s why the data is so important. What I’ve learned from our community partners is they want transparency of data and accountability for change.” For Cone Health, transparency of data has meant everything from being willing to share de-identified trend data from its hospitals with community organizing groups to advance their work, to publishing system-wide data about racial health disparities. And throughout the pandemic, Cone Health has been publishing a public-facing COVID dashboard. (These steps—increasing transparency and building mechanisms to engage community members in governance and monitoring—are essential components of “institutional accountability for health equity,” defined by HealthBegins in spring 2021.)

2) Ask for input on the problem, not just the solution.

Elevating and centering community voice in decision-making goes beyond asking for input on solutions; it is critical to ask community members what they see as the problem and about their most pressing priorities. Vail stressed that it’s not just about asking people, “How would you solve for this? But also, is this even what you would solve for?” What we learn when we stop to really be an authentic partner and listen is so valuable.”

3) Get (and stay) uncomfortable.

“As we’ve found across the country, centering the voices of community members requires health system leaders to show courage—courage to approach this work with genuine respect, to facilitate and create a safe space for difficult conversations, to find comfort in discomfort, and to commit to meaningful action,” said Dr. Rishi Manchanda, CEO of HealthBegins. This finding rings true for Vail, who knows that regularly listening to community members and asking for their input often means hearing uncomfortable reflections about the organization. However, Vail notes that if an institution is truly committed to elevating community voices in its decision-making and being authentic partners, then some of the most important things it can do are to get comfortable with being uncomfortable, to stay at the table when it’s hard, and to not push back on the difficult truths people share

Featured Content

Staff Spotlight: Erica Jones, Following Her Path and Passion to Help People

“I wish people would try to advocate for themselves more, because I feel like there's this power struggle and people don't feel like they can.”

Staff Spotlight: Kyron Pierce, The Eagle Scout with a Passion For Helping People Lead Healthy Lives

“[Health equity] is very hard work and it might be some years for us to see the fruits of our labor, but it'll be worth it when you do produce it.”

Staff Spotlight: Alejandra Cabrera, Perfectly Imperfect Artist and Health Equity Advocate

When I work with people and communities, I always think back to this sense of not belonging and it drives me to continue to do the heart-work we need to do to advance health equity.